At Alpic, we believe the next generation of products and services will be built around AI-first experiences, interfaces where users collaborate with models instead of navigating traditional, predetermined UI workflows.

When OpenAI released the Apps SDK, we immediately started building with it. Over the course of three months, we developed two dozen ChatGPT Apps for both internal use and for our customers across B2B and B2C spaces such as travel, retail, and SaaS.

What we discovered early on is that building ChatGPT Apps is fundamentally different from building traditional web or mobile applications. Patterns that work well on the web (just-in-time data fetching, UI-driven state, explicit user configuration, etc.) often break down or actively harm the experience in an agentic environment.

This post is a distilled set of the 15 most important lessons we learned while building real-world ChatGPT Apps, followed by how we incorporated those lessons into an open-source framework for the community, Skybridge, and a Codex Skill to help developers ideate, build, test, and ship Apps significantly faster.

The three body problem

With traditional web apps, things were simple: you only had a user and a UI. In a ChatGPT app, a third body enters the system: the model.

One of the hardest parts of building for ChatGPT is managing how information flows between this trio. If a user clicks a “Select” button in your widget, the UI updates visually, but the model, the brain of the conversation, remains unaware unless you explicitly surface that context. If the user then asks, “Give me more details about this product,” the model has no idea what the user is actually looking at.

We call this context asymmetry where each body has partial knowledge of the system, and no single one has the full picture. Building good ChatGPT Apps isn’t about keeping everything in sync, but about deciding what information should be shared, when it should be shared, and who needs visibility into it. Solving this is the difference between a clunky app and a seamless agentic experience.

1. Not all context should be shared

Our initial instinct was to “just share everything everywhere.” That turned out to be one of our earliest mistakes.

In practice, different parts of a ChatGPT App often need intentionally different views of the same state. Why?

- For performance: UI widgets often require far more data than the model should ever need: for example, in a travel booking app that could be images, pricing variants, preloaded options. Sending all of this to the model would increase token usage, latency, and cognitive noise.

- For logic: some information must remain asymmetric by design. In one of our earliest apps, a Murder in the Valleys mystery game, the model needs to know who the killer is to roleplay correctly, while the UI and user must not. In a Time’s Up-style game, the situation is reversed: the UI shows the secret word to the user, while the model must remain unaware.

The lesson wasn’t “always sync everything,” but rather: decide explicitly who needs to know what. We formalized this using different tool output fields:

| Field | Purpose | Visible to |

|---|---|---|

| structuredContent | Typed data for the widget and model | Both widget and model (via toolOutput and callTool functions) |

| _meta | Response metadata | Widget only, hidden from the model |

For example, for the Time’s Up game, we were passing the secret word only to the widget in the _meta field, letting the model guess the word from the user’s hints.

2. Lazy-loading doesn’t translate well to AI apps

Coming from web development, we defaulted to lazy-loading: fetching data when the user clicks; loading details on demand; optimizing for minimal upfront payloads.

In ChatGPT, the paradigm is reversed: tool calls imply delays, often taking several seconds due to security sandboxing and model reasoning.

In practice, we learned to front-load aggressively: sending as much data as possible into the initial tool response, and hydrating the widget via window.openai.toolOutput. This almost always resulted in a faster and more responsive experience.

Of course, if the widget can safely fetch data from a public API endpoint, and doesn’t need to share information with the model, it’s always possible to use classic XHR calls inside your widget, but most of the time you want the model to be able to call tools autonomously to keep the experience conversational.

3. The model needs visibility

A subtle but critical problem arises when the user interacts with a widget (e.g., selecting a specific product in a list) and then asks a question in the chat. If the model doesn’t know what part of the UI the user is referring to, it won’t be able to answer correctly.

For this we used window.openai.setWidgetState(state), which allows you to store specific state data that is added to the model’s context on the next user-model interaction.

With apps growing in complexity, we saw that we were adding setWidgetState in a lot of places for the model to keep track of the navigation. So we decided to introduce a declarative way to describe UI context. Instead of updating the model imperatively on every interaction, we attach a data-llm attribute directly to components:

<div

data-llm={

selectedTab === "details"

? "User is viewing product details"

: "User is viewing reviews"

}

>For this to work behind the scenes, we built a Vite plugin that scrapes these attributes and automatically updates the widgetState. From the model’s perspective, it simply receives the relevant UI context at the right time, without developers having to manually synchronize every interaction.

You can find this Vite plugin (and many other tips we share in this article) in the open-source framework we created to share our learnings with the community.

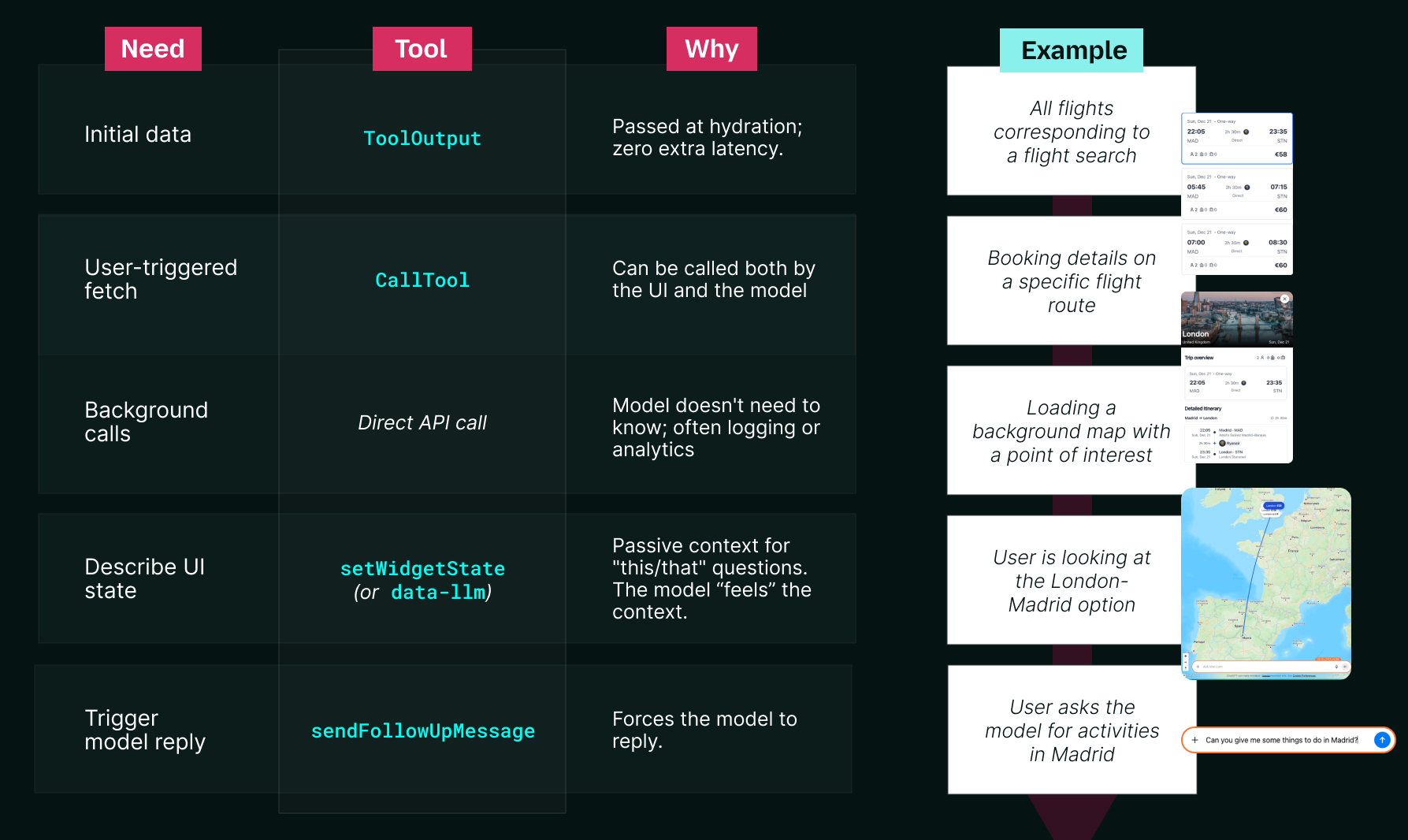

4. Different interactions require different APIs

ChatGPT Apps involve multiple interaction paths between the widget, the server, and the model. These paths are not interchangeable: each exists to support a different kind of interaction.

One of the key lessons in building ChatGPT Apps is making these communication paths explicit, and being intentional about which mechanism is responsible for which part of the experience.

Mapping out that path looks something like this:

These lessons establish the foundations of a ChatGPT App: how context is shared, how the model gains visibility, and how different interactions propagate through the system. The next section builds on this foundation and focuses on the implications for UI design.

Reinventing UI for AI

ChatGPT Apps are a completely new environment, so we quickly learned to set aside our preconceived notions about UI and use the new capabilities fully. This section covers interface design assumptions that we needed to learn (and unlearn) to create effective apps.

5. UI must adapt to multiple display modes, and their constraints

ChatGPT Apps don’t live in a single layout. Depending on how and when they’re invoked, the same widget can be rendered in three different display modes.

Apps can appear inline in the conversation, in picture-in-picture (PiP) on top of it, or in fullscreen when more space is needed. While PiP and fullscreen enable richer interfaces, they also introduce UI overlays that the widget doesn’t control. Accounting for device-specific safe zones, such as the persistent close button on mobile, is essential to avoid clipped content and to optimize interactions.

Over time, we identified patterns around display modes and when to use them:

| What it looks like | When to use it | |

|---|---|---|

| Inline | Default display mode. The widget stays in the conversation history. | for quick interactions |

| Fullscreen | Widget takes up the entire screen, with the chat bar at the bottom. | if your widget is complex and needs a lot of space (e.g., maps) |

| Picture-in-Picture | Same size as inline, but the widget stays on top of the conversation | if your widget remains relevant during conversational follow-ups after generation |

6. UI consistency matters in an embedded environment

Early on, one uncertainty we ran into was how much visual freedom a ChatGPT App should take. As a new interface for users, it needed to feel familiar and consistent, both within our own apps and with the surrounding ChatGPT ecosystem. Unlike a standalone product, a widget lives inside an existing interface, where visual inconsistencies stand out immediately.

Fortunately, the OpenAI Apps SDK UI Kit gave us a clear baseline.

Built on Tailwind CSS, it provides ready-to-use components, icons, and design tokens that align with ChatGPT’s design system. Using it allowed us to move quickly while ensuring our widgets felt native and visually consistent with the surrounding interface, even when building custom components (for example, for our Mapbox integration).

7. Language-first filtering

Traditional dashboards are built on sidebars full of checkboxes and range sliders. In agentic UI, this is often a regression. When users can express intent directly in natural language, for example, “Sunny destinations in Europe for under $200,” forcing them through multiple UI controls adds friction. They should be able to just say it.

We therefore decided to go the way of “no filters” for most of our apps. Instead of a sidebar with options to filter and sort, we provide the model with a List of Values (LOV) for our tool parameters.

This allows the model to take the user’s message as input directly, preventing it from “guessing” what options are available. In other words, it allows it to map natural language directly to our backend’s API requirements. If a user says “sunny,” the model knows to call the tool with weather=“sunny”.

8. Files can unlock richer interactions

One lesson that emerged as we built more complex apps is that files shouldn’t be treated as secondary inputs. In ChatGPT Apps, files can unlock new interactions. Instead of starting from forms or filters, experiences can start from something the user already has.

For example, in an ecommerce app, a user can upload a photo of a product in the chat, have the model identify it, and then continue into product matching or discovery directly in the widget.

This is made possible by letting files flow through both sides of the system. On the model side, tools can directly consume files uploaded in the chat via openai/fileParams, allowing the model to reason over images or other user-provided assets. On the UI side, widgets can also work with files directly using window.openai.uploadFile and window.openai.getFileDownloadUrl, making it possible to request uploads as part of the UI flow or generate files users can download and reuse.

Going to production

Next, as apps move beyond local development, a different set of considerations comes into play around security, configuration, and tooling. That’s what this third set of lessons covers.

9. CSPs are the new CORS

For security reasons, OpenAI renders Apps inside a double-nested iframe. Content Security Policies (CSPs) are a native mechanism of iframe isolation, and this setup enforces them strictly, often surfacing as the classic “it works locally but breaks in production” syndrome.

Unlike traditional web dev where you might get away with a loose policy, the Apps SDK requires you to be surgical.

In the app manifest, this means carefully declaring which domains are allowed for each type of interaction:

| Field | Purpose | Example | Common mistakes |

|---|---|---|---|

| connectDomains | API & XHR requests | https://api.weather.com | Forgetting the staging API vs. production. |

| resourceDomains | Images, fonts, scripts | https://cdn.jsdelivr.net | Using a generic CDN like delivr.net without whitelisting it |

| frameDomains | Embedding iframes | https://www.youtube.com | Embedding a YouTube video or Mapbox instance without whitelisting it. |

| redirectDomains | External links opened without warnings | https://app.alpic.ai | Forgetting the checkout or OAuth callback domain. |

Treating CSP configuration as a first-class concern early on saved us a significant amount of production debugging later.

10. Small widget flags have outsized impact

Beyond CSPs, a small set of widget-level settings determines how control is shared between the widget, the model, and the host environment. These flags are easy to overlook, but they define critical boundaries for navigation, tool access, and publishing.

Host and navigation boundaries

widgetDomainis required for submission. It defines the default location where the “Open in <App>” button points in fullscreen mode and participates in origin whitelisting, since widgets are rendered under<widgetDomain>.web-sandbox.oaiusercontent.com. We usedsetOpenInAppUrlto route users to the appropriate path based on context.

Model and tool boundaries

- Tool annotations must follow publishing guidelines. Flags like

readOnly,destructiveHint, andopenWorldHintare required and validated during submission. - Tool visibility matters: tools that should not be callable by the model must be explicitly marked as private.

Widget execution boundaries

widgetAccessiblecontrols whether the widget can call tools on its own usingcallTool.

Individually these settings are small, but together they determine whether an app behaves correctly once published.

Optimizing for fast iteration

The Apps SDK is evolving rapidly, and we’ve been excited to build alongside it. To support a smooth and efficient development workflow, we decided to develop our own open-source framework and share it with the community. Here are some of the learnings to avoid some of the developer experience issues we met in the beginning.

11. Fast iteration requires hot reload

One of the first things we tackled was iteration speed. The combination of long-TTL resource caching and the use of JSON-RPC to forward the resources makes standard hot module reload (as found in Vite or Next.js) incompatible with ChatGPT Apps out of the box.

After spending considerable time understanding Vite’s internals, we built a Vite plugin that enables live reload of widgets directly inside ChatGPT. The plugin intercepts resource requests to the MCP server and injects real-time updates into the ChatGPT iframe. Seeing a change in the IDE immediately reflected inside ChatGPT dramatically shortened our feedback loop.

12. Not every test belongs in ChatGPT

Testing on ChatGPT is the gold standard, but for the first iterations, a local emulator can help you move more quickly, especially when you are working on tool definitions that require app reloads in Developer Mode.

To speed up early iterations, we built a lightweight local emulator that mocks the ChatGPT host environment, complete with debugging tools and apps-specific logs. This allowed us to iterate on React state and layout in milliseconds, reserving real ChatGPT tests for validating model interactions and edge cases.

13. Mobile testing requires explicit support

Mobile testing introduced a separate challenge: while tunnelling your local server is necessary for testing in ChatGPT, Vite’s default use of localhost makes the same URL inaccessible from other devices.

We addressed this by extending our Vite plugin to support domain forwarding on tunnelled ports, which unblocked testing on both iOS and Android devices and made mobile validation part of our regular workflow.

14. Familiar abstractions (like React hooks) speed up frontend work

The Apps SDK exposes powerful capabilities, but largely through low-level JavaScript APIs. As longtime React users, we wanted to get closer to concepts we already mastered.

So we introduced some React-friendly abstractions—hooks like useCallTool, useWidgetState, and useLocale, as well as more advanced state management like createStore built on Zustand for complex data flows. Reintroducing familiar frontend patterns reduced boilerplate and made widget development feel closer to modern web workflows.

Turning lessons into a Codex Skill

15. Turn lessons into reusable tooling

As these patterns emerged across multiple apps, it became clear that repeatedly rediscovering them was slowing us down. To make ChatGPT App development faster and more predictable we decided to encode these lessons directly into our tooling, and not just for ourselves but for the community.

This led to two complementary efforts:

- The Skybridge Framework: an open-source React framework packages many of the patterns described in this post into reusable building blocks, including our hooks (

useCallTool,useToolInfo), the dev tools (HMR and local emulator), and the data-llm attribute. - The chatgpt-apps-builder Codex Skill: on top of the framework, we built a dedicated Codex Skill to support the full app lifecycle:

- Ideation: brainstorming how to make an app “agentic” rather than just a web port.

- Code generation: writing both the React frontend and the MCP server backend simultaneously, pre-configured with all the right UX and UI patterns.

- Local testing: starting dev servers and connecting local apps to ChatGPT for real-time iteration via hot reload.

- QA and publishing: running structured checks against OpenAI’s submission guidelines, including CSP validation, safe-zone considerations, and production testing.

- Deployment of the app: assisting with the final steps required to ship and iterate on an app.

To install and use the Skill, simply use the following command:

npx skills add alpic-ai/skybridgeConclusion

Building ChatGPT Apps requires rethinking how context flows, how interfaces behave, and how users and models collaborate. Many of the lessons in this post came from gaps between familiar web patterns and the realities of agentic systems.

By sharing these lessons, and by encoding them into our open-source framework and Codex skill, we hope to help teams spend less time rediscovering the same issues and more time exploring what this new interaction model makes possible. The most compelling ChatGPT Apps won’t be simple ports of existing products, but experiences deliberately designed around this new AI-first experience.